As Pastor John Amanchukwu spoke, his voice reverberated throughout the gala room of Sandstone Mountain Ranch, an exotic hunting preserve and event space near Llano, a small Texas Hill Country town about 80 miles northwest of Austin.

“Not only should we put God first in Congress, the General Assembly, throughout this land, in the halls of government, in the halls of power,” Amanchukwu boomed, “we should also put God first in our libraries.”

The crowd erupted in applause.

Sitting at the tables before Amanchukwu were not congregants but donors, each having spent between $100 and $1,250 per person to attend. A table for eight cost $10,000.

On that crisp fall afternoon in November 2023, Amanchukwu — a North Carolinian who has embraced the label of “Book Banning Pastor” — was among several prominent conservative figures who traveled from across the country to raise money for Llano County’s legal defense in a federal book ban case.

At least, that’s what attendees believed they were raising money for.

But one year after the event, Llano County still hasn’t seen a dime of the funds collected, the American-Statesman found through public records and interviews with officials. The county’s outside lawyer, well-known conservative attorney Jonathan Mitchell, also has not received any money from the fundraiser, he told the Statesman.

Instead, the money went to conservative nonprofit America First Legal — which has no present role in litigating or funding the case. The nonprofit, which recorded $44.4 million in revenue in 2022, has never contacted county leadership in writing, according to public records requests.

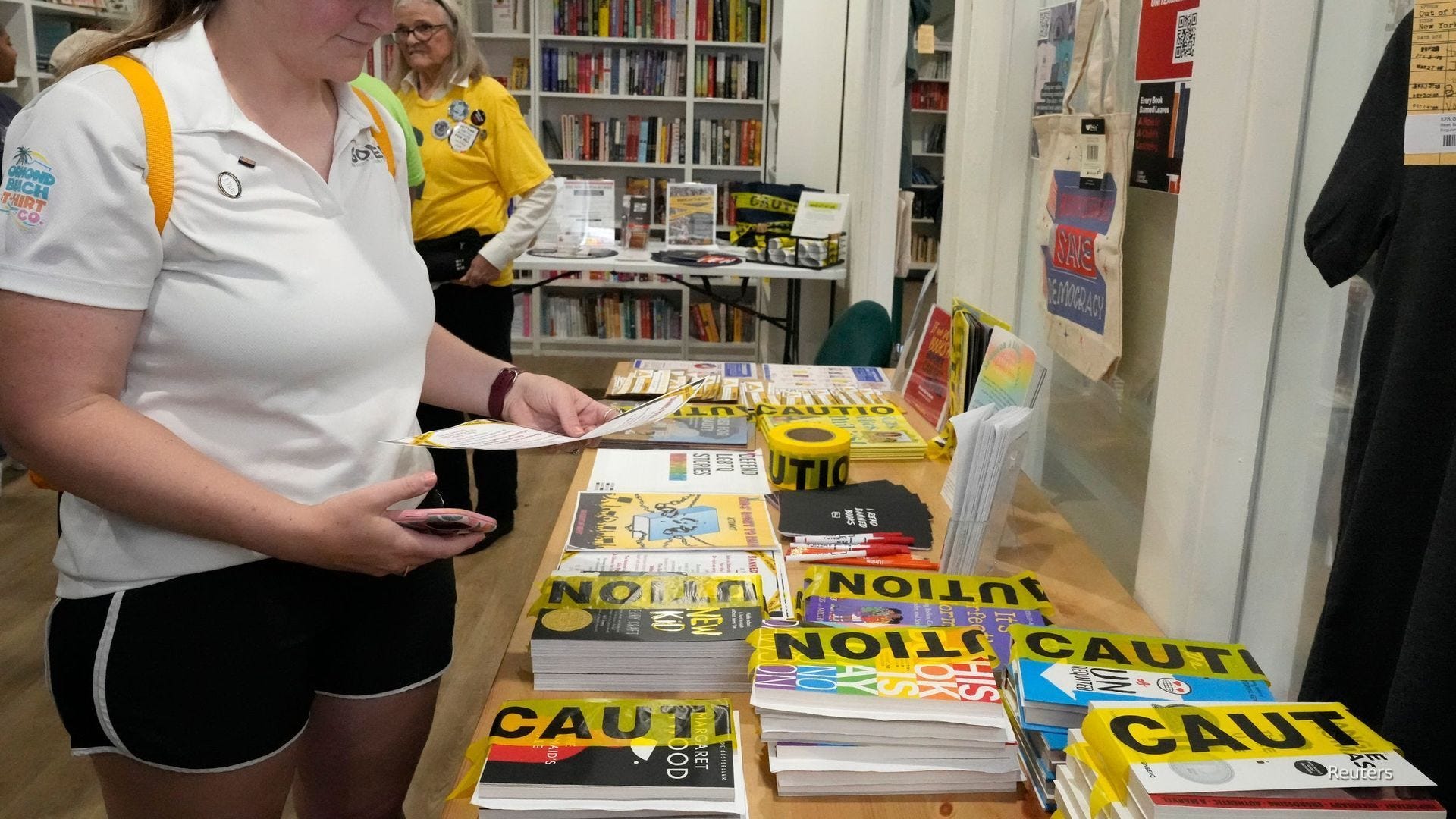

The case — which made Llano County, a rural Central Texas community of about 22,000, a national flashpoint in the culture wars — centers around the county’s removal of 17 titles from its public libraries in 2021. Some were children’s books containing nudity in illustrations, including Maurice Sendak’s 1970 classic “In the Night Kitchen,” while others were works on race, gender and sexuality, ranging from “Being Jazz: My Life as a Transgender Teen” to “They Called Themselves the KKK: The Birth of an American Terrorist Organization.”

In April 2023, a federal judge in Austin ordered the county to restore the books while the lawsuit played out, ruling in favor of seven residents who sued. Llano County then appealed the decision to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

Later that year, several months after Llano County officials threatened to shut down public libraries over mounting legal costs, defendant Bonnie Wallace organized a fundraiser. The county had spent nearly $200,000 to defend its removal of what Wallace — sued in her capacity as a Library Advisory Board member— called “pornographic and other harmful content.” A trial was likely years away.

“A loss would ensure that the pornography-pushers would continue pursuing more radical means to indoctrinate our children,” Wallace wrote in a flyer she distributed. “If Llano County loses, the entire country loses.”

The flyer said “100%” of the contributions would go to the county’s legal defense.

Wallace, on the flyer, instructed donors and ticket-buyers to make checks payable to America First Legal. The conservative nonprofit was founded shortly after the 2020 election by Stephen Miller, an adviser to President-elect Donald Trump in his first term. Miller will return to the White House as deputy chief of staff for policy when Trump returns to office in January.

Though based in Washington, D.C., America First Legal has ties to Texas officials: Its first challenge to the Biden administration was state Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller’s successful discrimination lawsuit against a program that would have directed aid to Black and other minority farmers and ranchers. Later, America First Legal helped defend Texas’ Senate Bill 8 in a case filed by abortion rights advocacy groups, and its lawyers also filed a brief supporting Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton in a wrongful termination lawsuit filed by whistleblowers who related allegations to the FBI of possible misconduct by Paxton before they were fired from his office.

The group describes its purpose as “fighting back against lawless executive actions and the Radical Left” on its website.

The Llano County event flyer said donations to the nonprofit would help fund the county’s representation by Mitchell, the conservative lawyer who has worked with America First Legal in several high-profile cases.

Llano County Judge Ron Cunningham, however, told the Statesman in an August interview that the money “hasn’t been offered, and we haven’t accepted it.” He reaffirmed to the Statesman on Nov. 14 that the group had not reached out to him.

Though America First Legal’s Executive Director Gene Hamilton spoke at the fundraiser, the nonprofit has no role in litigating the case. (Video of the event shows that Hamilton described the case and emphasized his friendship with Mitchell, but he stated he was not personally litigating the case.)

America First Legal declined the Statesman’s request for an on-the-record interview and did not respond to written questions after repeated attempts to reach the group in October and November.

US schools banned 10,000 books last school year alone

It’s Banned Books Week in the U.S. and it comes as we’re learning more than 10,000 books were banned in public schools nationwide last year.

Straight Arrow News

Cunningham, county commissioners and Mitchell did not attend the fundraiser and were not involved with its organization, according to their statements and public records requests.

Furthermore, there is no record that America First Legal has made any agreement or plan to exchange funds in the future, the Statesman found through numerous public records requests to the county judge, commissioners, library, attorneys and treasurer.

Mitchell, who is representing the county, cemented his reputation in conservative circles as the mastermind behind Senate Bill 8, the 2021 Texas law that used a novel private-enforcement mechanism to ban abortions after fetal cardiac activity had been detected. That law went into effect about nine months before Roe v. Wade was overturned. Mitchell also defended Trump in the Colorado ballot eligibility case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

He told the Statesman that Llano County taxpayers, not America First Legal, have footed the legal bills in this case.

“America First Legal has paid me nothing for my work on the Little v. Llano County litigation,” Mitchell wrote in an October email. “They are not part of this lawsuit and they are not financing the litigation in any way. My invoices have been paid entirely by Llano County.”

The 2023 fundraiser was a resounding success, collecting more than $82,000, Wallace, an event organizer, later boasted on the conservative Christian podcast “WallBuilders.”

“Llano County, we’re a very poor county, which is why I held the fundraiser last November,” Wallace told host Rick Green in a July episode. “We raised $82,275 for the county, so I was very proud of that. We’ll have another one at some point.”

For others, there is little to celebrate about the case and the fundraiser.

“This is a working-class town, and people are getting rich by doing this in our name, for our sake, when you have a large contingent of our community saying, ‘Stop doing this, we need vibrant libraries,'” Llano resident Gretchen Hinkle, who opposes the book removals, said of the fundraiser. “Why is the voice of AFL, of Jonathan Mitchell, so much more powerful than that of the citizens of this county?”

Attendees of the fundraiser believed the donations would benefit Llano County’s legal defense.

State Rep.-elect Wes Virdell, who will represent Llano County when he’s sworn in to office in January, posted on Facebook ahead of the event that the money raised would “offset the legal fees incurred” by the county. (Virdell declined to comment in response to the Statesman’s requests.)

A post in the Central Texas Tea Party Facebook group and another from a Republican women’s organization from the neighboring town of Horseshoe Bay also indicate the money raised would go to the county’s legal defense.

“Fundraiser event for our Llano neighbors who are fighting ‘dirty’ books in libraries. Many of the folks who are standing up are being sued,” Central Texas Tea Party member Sherry Eller captioned a link to the flyer. “If you have the means to help them, please attend and/or send a donation.”

News outlets including The Dallas Express and far-right news outlet Texas Scorecard also reported that the fundraiser would benefit the county. Axios, on the other hand, reported the fundraiser would raise money for America First Legal and for Mitchell, the county’s outside attorney.

The county’s legal defense has cost more than $270,000 in 2½ years, including travel costs and court fees, the Statesman’s analysis of invoices obtained through an open records request found.

Llano County pays Mitchell a rate of $450 per hour, according to invoices and a retainer agreement obtained by the Statesman. The nationally recognized attorney has said he typically charges $1,200 per hour, Texas Monthly previously reported.

Some Llano County residents have criticized the county for continuing to fight the lawsuit as costs accrue. County officials have frozen all new book purchases until the legal battle ends, saying new additions could affect the ongoing litigation.

“Public funds should be spent to reverse the removals, not to support their decision to pull the books,” Llano County retiree Alair Brown told the Statesman. “For one little group of people to pick and choose what’s appropriate for people, that goes against the grain of who we are as Americans.”

Others, however, like the fundraiser’s attendees, have rallied behind the effort. Some residents supported a proposal from commissioners to close all three county libraries while the lawsuit plays out, which officials tabled after significant pushback in April 2023.

America First Legal’s involvement is just more evidence that the small community is being used to advance a larger agenda, said Tow resident Lisa Miller, who opposes the removals.

“So much has been tried using Llano as a pawn in a big game,” Miller, a 67-year-old private housekeeper, said in an interview. “They’re using people, and they’re dividing them, and it’s working.”

When the Statesman asked America First Legal again Nov. 14 if it had taken steps to deliver the money, the nonprofit did not respond.

Wallace also did not respond to repeated phone and email inquiries from the Statesman about how the money raised would be used.

It’s unclear how she first connected with America First Legal, or whether she believed the group was involved in the case. Mitchell’s original retainer agreement, signed by the county but not by American First Legal, erroneously stated that the group would pay for his fee. Mitchell clarified to the Statesman that this was a “typo” left over from a retainer form he had used in previous cases. The county signed a new, corrected contract Nov. 20.

Whether the county will receive the money remains to be seen. Section 81.032 of the Texas Local Government Code allows counties to take donations for costs related to county business, which includes legal defense fees, attorney and Texas Ethics Commission Chair Randall Erben told the Statesman.

Regardless, the county’s legal costs are expected to continue to grow.

In June, a three-judge panel of the 5th Circuit found that the removals of eight of the 17 books were motivated by a desire to “suppress the ideas within them,” violating a 30-year-old precedent barring such removals.

Mitchell then appealed that decision to the court’s full bench. In a Sept. 24 rehearing in New Orleans, the attorney argued that library content decisions are “government speech, immune from First Amendment scrutiny,” and that as such, removals cannot constitute censorship. Republican attorneys general of 17 states put their weight behind Mitchell’s argument in a friend-of-the-court brief.

Attorneys for the plaintiffs and several civil rights groups say a possible ruling in Mitchell’s favor would allow groups in power to pass laws discriminating against minority groups and ideas, turning libraries from “institutions of knowledge” into “political institutions.”

If the 5th Circuit takes Llano County’s side, the case is likely to go to the Supreme Court, as the Statesman previously reported, which could significantly increase litigation costs. A decision in favor of the plaintiffs would send the case back to the trial court.

A petite woman with a bob of shining, perfectly coiffed gray hair, Wallace has gained notoriety over the last year as a champion for book removals alongside Amanchukwu and Pastor Richard Vega, another politically active preacher. Though her daughter graduated from high school years ago, Wallace has made regular appearances before school boards of districts throughout Texas as well as the State Board of Education to urge them to remove hundreds of books.

As a speaker at events hosted by conservative Christian groups, Wallace often boasts of her status as a defendant in the lawsuit, stating inaccurately that Llano County was “sued for relocating pornography out of the children’s section and into the adult section.”

But the fundraiser was a key moment in Wallace’s budding political career, as she mingled and prayed with some of the most well-known figures behind the movement to imbue Christian values in education and libraries.

“God, I would be remiss if we did not pray for Bonnie Wallace and … those who work alongside her to gain the victory in this case,” Amanchukwu said in an opening prayer at the 2023 fundraiser, with the crowd clapping and whooping after his “Amen.”

For an event held in Llano, a town of 3,000 within Llano County, the speaker list was impressive: One scheduled speaker was Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation. The Washington-based conservative think tank authored a now-infamous plan for consolidating presidential power under a second Trump administration, Project 2025. Ultimately, Roberts was unable to attend.

Other speakers included then-Republican Party Chair Matt Rinaldi and representatives from several conservative groups, including Patriot Academy, the Texas Family Project and the Texas Public Policy Foundation, which advocate for the state to embrace religious values.

At the end of the fundraiser, after showing attendees a video about how pornography can be addictive for young people, Wallace and two co-defendants, Rhonda Schneider and Rochelle Wells, joined hands in prayer onstage. All were members of the campaign to remove the books and were later appointed to the county’s Library Advisory Board.

“Good Father, we pray that You give us the words because You said You’ve given us all authority to trample on scorpions and snakes and all the powers of the enemy,” Wells said, her voice trembling with emotion. “And we decree that the children of Texas will be saved now, that the demonic powers at work will be trampled on by the sons and daughters of God.”

“Victory,” Wallace interjected.

“Victory in the name of Jesus, for the sake of Jesus,” Wells said. “Amen.”

Before stepping offstage, Wallace asked those in attendance to consider running for their local school boards.

“Think about it, pray about it and give me a call,” she said. “And God bless you.”